Background

The Chancellor of the Exchequer announced on 4 September that a consultation into the calculation of the Retail Prices Index (RPI) will be launched in January 2020.

RPI, historically written into scheme rules and introduced back in 1947, dictates how pension increases are calculated for a large proportion of the pensions in payment today.

The introduction of the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), and its close cousin the Consumer Prices Index including housing costs (CPIH), as a more representative figure of household price inflation, threw into sharp focus how flawed RPI was, and is, at reflecting those costs.

So, what’s the issue with RPI?

When CPI was adopted as the UK’s official inflation target by the then Labour Government in 2003 it was widely acknowledged as a sensible move. Much of Europe and the rest of the world already used a CPI approach as their measure for inflation and the methodology for the calculation of RPI was often criticised. Whilst RPI lost its national statistic status in 2013, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) continued to calculate and publish the figures and it therefore remains in existence.

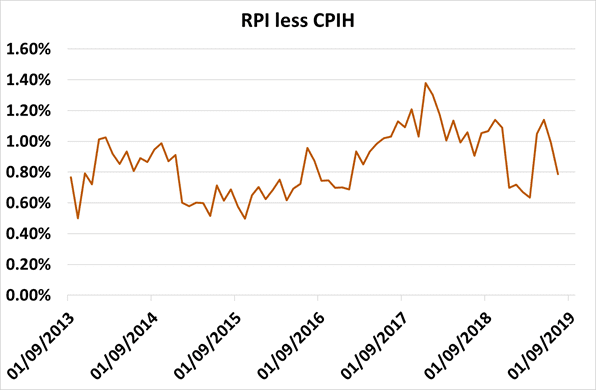

Both CPI and CPIH have been consistently lower than RPI over recent times. In fact, CPIH has been about 0.7% to 1% per annum lower than RPI over the last six years since it was launched in 2013 (as shown in the graph below). A fact that has not been lost on both sponsoring employers and trustees of pension schemes grappling with ever increasing scheme liabilities.

Whilst scheme rules dictate the extent to which CPI and RPI can be used for pension increases, all other things being equal, lower future pension increases may mean lower future funding requirements.

This simple fact has led to many high-profile court cases (including BT and Barnardo’s) regarding whether trustees and/or employers can switch from RPI to CPI to reduce costs.

There are of course, other potentially unintended consequences.

With portions of scheme liabilities moving in line with RPI, many trustees have sensibly managed this risk by investing in assets that hedge these movements (often choosing index-linked gilts, or swaps, which use RPI as the measure of inflation). Future changes in indices could mean the prospect of an inefficient hedge and an increased risk to schemes with potentially significant and costly implications.

The consultation timetable

Following its announcement last year that both public sector pension schemes and future index-linked gilts would be based on CPIH where practically possible, the Government has now issued its consultation on aligning the calculation of RPI to CPIH.

The Government however seems in no rush to make any decisions. The consultation confirms that change will be made over the course of the decade to 2030, with no change at all until at least 2025.

What now?

Any concrete changes to RPI will not happen quickly. Being so ingrained into how pension schemes have operated over their history means there may be many strands to unpick.

As a very initial step trustees should understand how inflation (whether RPI or CPI) impacts their scheme both in the increases it provides to members and any investment decisions they have made.

Detailed investment, actuarial and legal advice may be required, but with the change likely to happen at the very latest in 2030 there could be an argument to make an immediate allowance for potentially lower market-implied inflation assumptions in the future.

For further assistance in relation to these issues, please contact us.